It’s not just bad behavior – why social media design makes it hard to have constructive disagreements online

Johanna Svennberg/iStock via Getty Images

Amanda Baughan, University of Washington

Good-faith disagreements are a normal part of society and building strong relationships. Yet it’s difficult to engage in good-faith disagreements on the internet, and people reach less common ground online compared with face-to-face disagreements.

There’s no shortage of research about the psychology of arguing online, from text versus voice to how anyone can become a troll and advice about how to argue well. But there’s another factor that’s often overlooked: the design of social media itself.

My colleagues and I investigated how the design of social media affects online disagreements and how to design for constructive arguments. We surveyed and interviewed 257 people about their experiences with online arguments and how design could help. We asked which features of 10 different social media platforms made it easy or difficult to engage in online arguments, and why. (Full disclosure: I receive research funding from Facebook.)

We found that people often avoid discussing challenging topics online for fear of harming their relationships, and when it comes to disagreements, not all social media are the same. People can spend a lot of time on a social media site and not engage in arguments (e.g. YouTube) or find it nearly impossible to avoid arguments on certain platforms (e.g. Facebook and WhatsApp).

Here’s what people told us about their experiences with Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube, which were the most and least common places for online arguments.

Seventy percent of our participants had engaged in a Facebook argument, and many spoke negatively of the experience. People said they felt it was hard to be vulnerable because they had an audience: the rest of their Facebook friends. One participant said, on Facebook, “Sometimes you don’t admit your failures because other people are looking.” Disagreements became sparring matches with a captive audience, rather than two or more people trying to express their views and find common ground.

People also said that the way Facebook structures commenting prevents meaningful engagement because many comments are automatically hidden and cut shorter. This prevents people from seeing content and participating in the discussion at all.

In contrast, people said arguing on a private messaging platform such as WhatsApp allowed them “to be honest and have an honest conversation.” It was a popular place for online arguments, with 76% of our participants saying that they had argued on the platform.

The organization of messages also allowed people to “keep the focus on the discussion at hand.” And, unlike the experience with face-to-face conversations, someone receiving a message on WhatsApp could choose when to respond. People said that this helped online dialogue because they had more time to think out their responses and take a step back from the emotional charge of the situation. However, sometimes this turned into too much time between messages, and people said they felt that they were being ignored.

Overall, our participants felt the privacy they had on WhatsApp was necessary for vulnerability and authenticity online, with significantly more people agreeing that they could talk about controversial topics on private platforms as opposed to public ones like Facebook.

YouTube

Very few people reported engaging in arguments on YouTube, and their opinions of YouTube depended on which feature they used. When commenting, people said they “may write something controversial and nobody will reply to it,” which makes the site “feel more like leaving a review than having a conversation.” Users felt they could have disagreements in the live chat of a video, with the caveat that the channel didn’t moderate the discussion.

Unlike Facebook and WhatsApp, YouTube is centered around video content. Users liked “the fact that one particular video can be focused on, without having to defend, a whole issue,” and that “you can make long videos to really explain yourself.” They also liked that videos facilitate more social cues than is possible in most online interactions, since “you can see the person’s facial expressions on the videos they produce.”

YouTube’s platform-wide moderation had mixed reviews, as some people felt they could “comment freely without persecution” and others said videos were removed at YouTube’s discretion “usually [for] a ridiculous or nonsensical reason.” People also felt that when creators moderated their comments and “just filter things they don’t like,” it hindered people’s ability to have difficult discussions.

Redesigning social media for better arguing

We asked participants how proposed design interactions could improve their experiences arguing online. We showed them storyboards of features that could be added to social media. We found that people like some features that are already present in social media, like the ability to delete inflammatory content, block users who derail conversations and use emoji to convey emotions in text.

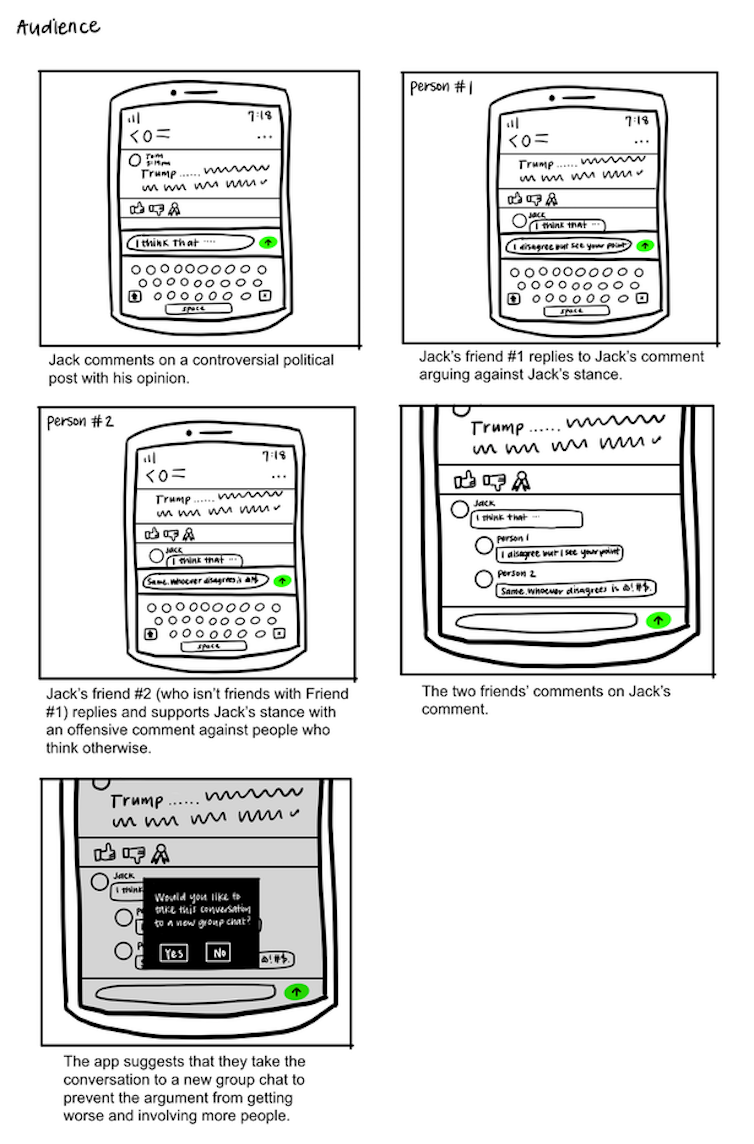

People were also enthusiastic about an intervention that helps users to “channel switch” from a public to private online space. This involves an app intervening in an argument on a public post and suggesting users move to a private chat. One person said “this way, people don’t get annoyed and included in online discussion that doesn’t really involve them.” Another said, “this would save a lot of people embarrassment from arguing in public.”

‘Someone Is Wrong on the Internet: Having Hard Conversations in Online Spaces’, CC BY-ND

Intervene, but carefully

Overall, the people we interviewed were cautiously optimistic about the potential for design to improve the tone of online arguments. They were hopeful that design could help them find more common ground with others online.

Yet, people are also wary of technology’s potential to become intrusive during an already sensitive interpersonal exchange. For instance, a well-intentioned but naïve intervention could backfire and come across as “creepy” and “too much.” One of our interventions involved a forced 30-second timeout, designed to give people time to cool off before responding. However, our subjects thought it could end up frustrating people further and derail the conversation.

Social media developers can take steps to foster constructive disagreements online through design. But our findings suggest that they also will need to consider how their interventions might backfire, intrude or otherwise have unintended consequences for their users.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]Amanda Baughan, PhD Student in Computer Science & Engineering, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How to eat for a better Earth

Views: 3

0

0

Share This

Read Time:4 Minute, 0 Second

The four-day work week – has its moment arrived? Podcast

Time for the three-day weekend.

fizkes/Shutterstock

Daniel Merino, The Conversation and Gemma Ware, The Conversation

Over the last few years, companies and governments in a number of countries have begun to experiment with the idea of a four-day work week – and some of the results are in. In this episode of The Conversation Weekly podcast, we talk to experts about these recent trials, explore how they fit into the long history of ever-shrinking work hours, and wonder what this all might mean for the future of work.

Then, we look at the history and politics of how informal settlements in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, got their names.

It’s an alluring idea. Working four days a week instead of five, without a cut in pay. And it’s a concept that’s been gaining traction in recent years, with a number of companies around the world experimenting by moving employees onto a four-day week.

In June, when a report was published about a public sector trial in Iceland, headlines heralded the success of the four-day week. But it wasn’t quite that simple, according to Anthony Veal, adjunct professor at the University of Technology Sydney Business School in Australia. “What it was not was a trial of a four-day week,” he tell us, explaining that there was actually a more limited reduction in working hours. Still, despite the misleading headlines, Veal says the trial was “highly successful in its own terms”, especially when put into context of the history of how the five-day week became standard in the 20th century.

Read more:

The success of Iceland’s ‘four-day week’ trial has been greatly overstated

Elsewhere, in March, the Spanish government gave the green light to a trial of a four-day week proposed by a small left-wing political party called Más País. José-Ignacio Antón, associate professor at the Department of Applied Economics at the University of Salamanca in Spain, explains what’s known so far about the proposed trial and why he’ll be watching the results closely. “I would have a look first at what happens with productivity,” he tells us, but adds that it may also have an impact on work-life balance and sick leave, and that such wider societal benefits should be taken into account too.

For Jana Javornik, associate professor of work and employment relations at the University of Leeds in the UK, some big questions need answering before a wholesale reduction of hours works for everyone. “I think the whole conversation around a four-day week has been ignoring gender,” says Javornik, who spent the past few years on secondment as Slovenia’s general director of higher education, a role which recently ended. Javornik tells us about a survey she did in Sweden with working mothers, which led her to believe that conversations about workload, organising work and a non-stop work culture must accompany any reduction in working hours.

In our second story, we head to Nairobi, in Kenya, where anger met a recent decision to rename a road in Nairobi after Francis Atwoli, a trade union leader. Many saw the renaming as overtly political. The road sign was vandalised and had to be replaced. But it’s not just the street names in Nairobi that come with their own politics. The names of the city’s informal settlements are themselves born out of a history of colonisation and struggle, as historian Melissa Wanjiru-Mwita from the Technical University of Kenya explains.

Read more:

The fascinating history of how residents named their informal settlements in Nairobi

And Catesby Holmes, international editor at The Conversation in New York, recommends two recent stories about immigration in the US.

This episode of The Conversation Weekly was produced by Mend Mariwany and Gemma Ware, with sound design by Eloise Stevens. Our theme music is by Neeta Sarl. You can find us on Twitter @TC_Audio, on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email on podcast@theconversation.com. You can also sign up to The Conversation’s free daily email here.

News clips in this episode are from KHOU11, Perpetual Guardian, CGTN Europe, CNN, RTVE Noticias and Kenya Citizen TV.

You can listen to The Conversation Weekly via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed, or find out how else to listen here.

Daniel Merino, Assistant Science Editor & Co-Host of The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation and Gemma Ware, Editor and Co-Host, The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

It’s not just bad behavior – why social media design makes it hard to have constructive disagreements online

Share

Share ThisRelated Posts:10 DOLLAR TREE HACKS THAT ACTUALLY WORK!Get Ready for Work and School this WinterResources for Addressing Mental Health Challenges at Work