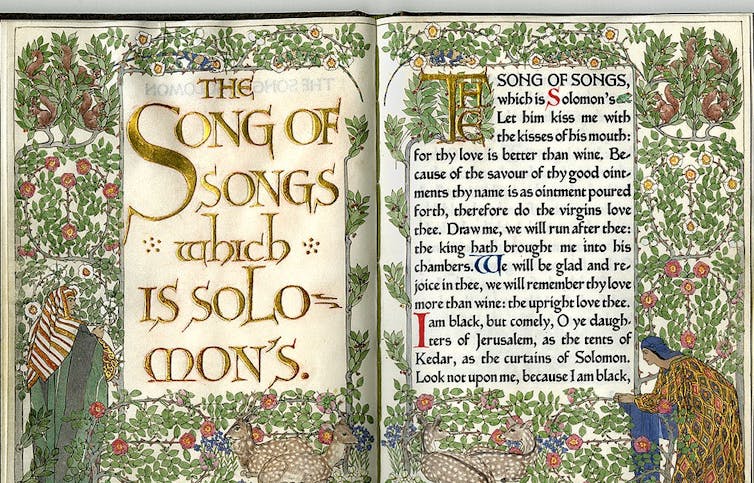

‘Song of Songs’ illustrated by Florence Kingsford/Southern Methodist University/Wikimedia Commons

Jonathan Kaplan, The University of Texas at Austin

Why is a love poem full of sex in the Bible? Readers have been struggling with the Song of Songs for 2,000 years

Many Americans have heard the expression “I am my beloved’s, and my beloved is mine” – in fact, a quick Google search turns up myriad websites offering wedding bands inscribed with the much-loved line. Search Etsy for Valentine’s Day gifts, and you’ll see jewelry, T-shirts and coffee mugs printed with the phrase. But perhaps not all of the quotation’s admirers know that its origins lie in a biblical text: the Song of Songs, which has created difficulties for readers for 2,000 years.

Also known as the Song of Solomon or Canticle of Canticles, the Song of Songs stands out in the Bible because of its extensive and candid sexual content. It is a work of sensual lyric poetry that portrays scenes of actual and imagined trysts between the poem’s female protagonist and her lover.

Graphic descriptions of both male and female bodies pervade the work and are certainly titillating, even bordering on pornographic. Sensual metaphors such as “grazing among the lilies” and “drinking … from the juice of my pomegranates” suggest sexual practices that are anything but vanilla.

It’s not just the emphasis on sex that makes the text unusual. The Song of Songs is the only work in the Bible that focuses exclusively on human-to-human love, not human-to-divine – at least on the surface level of the poem.

Ancient Jews and Christians were troubled by the inclusion of such a graphic love poem in the biblical canon and came up with their own ways to remedy the dilemma.

Barely a mention of God

The Bible includes other references to sex – including graphic depictions of sexual violence. And other books certainly contain depictions of human love, such as that of the patriarch Jacob, who labored for 14 years to win his wife Rachel in the Book of Genesis.

But when other biblical books talk about love and marriage, they primarily use this language to depict God’s relationship with people – specifically, the people of Israel, who have a special covenant with him according to the Torah. In contrast, the Song of Songs may possibly allude to Israel’s God only once, in chapter eight.

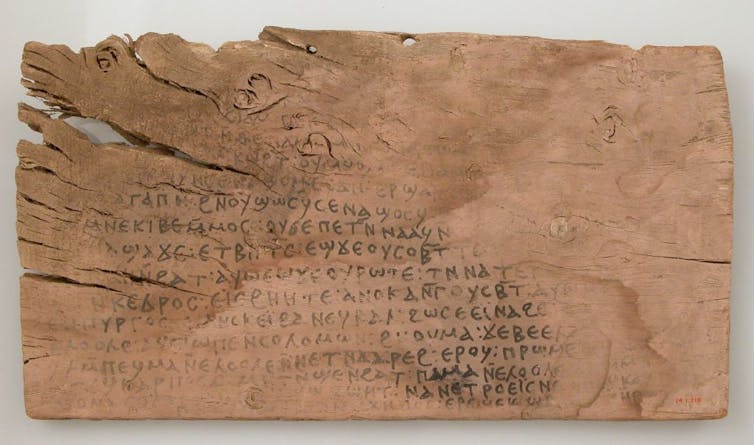

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Yet ancient interpreters of the Song of Songs did not interpret this poetic work as a depiction of human-to-human love. In fact, while researching my book about early rabbinic interpretation of the Song of Songs, I noticed that no such interpretations – Jewish or Christian – survive from before the modern era.

Instead, the earlier commentators “reread” the Song of Songs exclusively as a portrayal of divine-to-human love, God’s relationship with a beloved individual or community.

Covenant with the divine

Other scholars and I have argued that the earliest interpretations of the Song of Songs appear in late first-century works, such as allusions in the Book of Revelation – the final book in the New Testament, which describes prophetic visions of Jesus’ second coming – and 4 Ezra, another apocalyptic work included in some versions of the Bible.

In the first few centuries, rabbis began to interpret the Song of Songs as part of their commentaries on the Pentateuch, the first section of the Hebrew Bible. The Pentateuch describes the creation of the world and includes stories about the Israelites’ ancestors and their epic journey from Egypt to Israel. Over the course of several books, the Pentateuch shows them fleeing slavery, receiving revelation from God at Mt. Sinai, wandering in the desert for 40 years and finally entering the promised land.

These early rabbis envisioned that narrative as an extended, intimate story about God’s relationship with the people of Israel. And although they shied away from the more erotic dimensions of the Song of Songs, they used its language to depict God’s relationship with the people of Israel as more than a simple contractual arrangement. In my 2015 book, “My Perfect One,” I argued that the earliest rabbis characterized these bonds as deeply affectionate and marked by profound emotional commitment. For instance, in one passage, they interpret Song of Songs 2:6 – “His left hand was under my head, and his right hand embraced me” – as describing God’s embrace of Israel at Mt. Sinai.

A lover’s yearning

In a similar fashion, Christian scholars avoided the carnal dimensions of this poetic work. Rather than seeing the Song of Songs as a statement of God’s love for Israel, early Christians understood it as an allegory of Christ’s love for his “bride,” the church.

Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Other allegorical readings have also emerged throughout history. Origen, for instance, a third-century Christian writer, proposed that the Song of Songs could be interpreted as the soul’s yearning for God. Similar to other interpreters, Origen associated the soul with the female protagonist, and the divine with her male “beloved.”

Another Christian approach to the Song of Songs was that the poem described God’s loving relationship with Jesus’ mother, Mary.

These diverse interpretations may also have influenced medieval Jewish mystics. In Judaism, the divine presence or “Shekinah” is often thought of as feminine – an idea that became important to these mystics, who relied on the Song of Songs to describe the Shekinah.

Reading the poem today

In the modern period, even more understandings of the poem have emerged, including some about human-to-human love. For instance, feminist readings have highlighted the female character’s power, autonomy and sensuality. Conservative Christians, meanwhile, often approach the poem as an ideal expression of acceptable love between a husband and wife.

From the first few centuries up to today, these many meanings highlight readers’ creativity – and the evocative power of the Song of Songs’ poetic language.

Jonathan Kaplan, Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible and Ancient Judaism, The University of Texas at Austin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why You Should NOT Fear Death