Luis Alvarez/DigitalVision via Getty Images

Barry Markovsky, University of South Carolina

Would you think it weird if I refused to travel on Sundays that fall on the 22nd day of the month?

How about if I lobbied the homeowner association in my high-rise condo to skip the 22nd floor, jumping from the 21st to 23rd?

It’s highly unusual to fear 22 – so, yes, it would be appropriate to see me as a bit odd. But what if, in just my country alone, more than 40 million people shared the same baseless aversion?

That’s how many Americans admit it would bother them to stay on one particular floor in high-rise hotels: the 13th.

According to the Otis Elevator Co., for every building with a floor numbered “13,” six other buildings pretend to not have one, skipping right to 14.

Many Westerners alter their behaviors on Friday the 13th. Of course, bad things do sometimes happen on that date, but there’s no evidence they do so disproportionately.

As a sociologist specializing in social psychology and group processes, I’m not so interested in individual fears and obsessions. What fascinates me is when millions of people share the same misconception to the extent that it affects behavior on a broad scale. Such is the power of 13.

Origins of the superstition

The source of 13’s bad reputation – “triskaidekaphobia” – is murky and speculative. The historical explanation may be as simple as its chance juxtaposition with lucky 12. Joe Nickell investigates paranormal claims for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, a nonprofit that scientifically examines controversial and extraordinary claims. He points out that 12 often represents “completeness”: the number of months in the year, gods on Olympus, signs of the zodiac and apostles of Jesus. Thirteen contrasts with this sense of goodness and perfection.

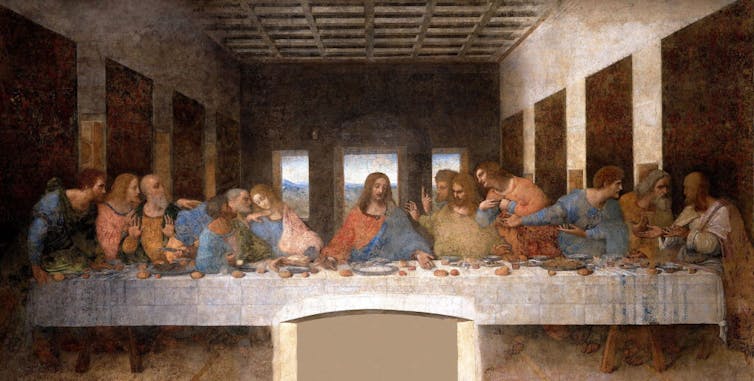

The number 13 may be associated with some famous but undesirable dinner guests. In Norse mythology, the god Loki was 13th to arrive at a feast in Valhalla, where he tricked another attendee into killing the god Baldur. In Christianity, Judas – the apostle who betrayed Jesus – was the 13th guest at the Last Supper.

Universal History Archive/Getty Images

But the truth is, sociocultural processes can associate bad luck with any number. When the conditions are favorable, a rumor or superstition generates its own social reality, snowballing like an urban legend as it rolls down the hill of time.

In Japan, 9 is unlucky, probably because it sounds similar to the Japanese word for “suffering.” In Italy, it’s 17. In China, 4 sounds like “death” and is more actively avoided in everyday life than 13 is in Western culture – including a willingness to pay higher fees to avoid it in cellphone numbers. And though 666 is considered lucky in China, many Christians around the world associate it with an evil beast described in the biblical Book of Revelation. There is even a word for an intense fear of 666: hexakosioihexekontahexaphobia.

Social and psychological explanations

There are many kinds of specific phobias, and people hold them for a variety of psychological reasons. They can arise from direct negative experiences – fearing bees after being stung by one, for example. Other risk factors for developing a phobia include being very young, having relatives with phobias, having a more sensitive personality and being exposed to others with phobias.

Part of 13’s reputation may be connected to a feeling of unfamiliarity, or “felt sense of anomaly,” as it is called in the psychological literature. In everyday life, 13 is less common than 12. There’s no 13th month, 13-inch ruler, or 13 o’clock. By itself a sense of unfamiliarity won’t cause a phobia, but psychological research shows that we favor what is familiar and disfavor what is not. This makes it easier to associate 13 with negative attributes.

People also may assign dark attributes to 13 for the same reason that many believe in “full moon effects.” Beliefs that the full moon influences mental health, crime rates, accidents and other human calamities have been thoroughly debunked. Still, when people are looking to confirm their beliefs, they are prone to infer connections between unrelated factors. For example, having a car accident during a full moon, or on a Friday the 13th, makes the event seem all the more memorable and significant. Once locked in, such beliefs are very hard to shake.

Then there are the potent effects of social influences. It takes a village – or Twitter – to make fears coalesce around a particular harmless number. The emergence of any superstition in a social group – fear of 13, walking under ladders, not stepping on a crack, knocking on wood, etc. – is not unlike the rise of a “meme.” Although now the term most often refers to widely shared online images, it was first introduced by biologist Richard Dawkins to help describe how an idea, innovation, fashion or other bit of information can diffuse through a population. A meme, in his definition, is similar to a piece of genetic code: It reproduces itself as it is communicated among people, with the potential to mutate into alternative versions of itself.

The 13 meme is a simple bit of information associated with bad luck. It resonates with people for reasons given above, and then spreads throughout the culture. Once acquired, this piece of pseudo-knowledge gives believers a sense of control over the evils associated with it.

False beliefs, true consequences

Groups concerned with public relations seem to feel the need to kowtow to popular superstitions. Perhaps owing to the near-tragic Apollo 13 mission, NASA stopped sequentially numbering space shuttle missions, dubbing the 13th shuttle flight STS-41-G. In Belgium, complaints from superstitious passengers led Brussels Airlines to revamp its logo in 2006. It had been a “b”-like image made of 13 dots. The airline added a 14th. Like many other airlines, its planes’ row numbering skips 13.

Because superstitious beliefs are inherently false, they are as likely to do harm as good – consider health frauds, for example. I’d like to believe influential organizations – perhaps even elevator companies – would do better to warn the public about the dangers of clinging to false beliefs than to continue legitimizing them.

Barry Markovsky, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Sociology, University of South Carolina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why does money exist?